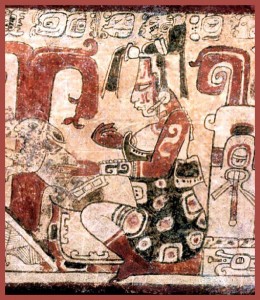

Legend the 1-st. Ixchel as a Young Woman.

Legend the 1-st. Ixchel as a Young Woman.

Ixchel is the Mayan goddess associated with the moon, sex, chidbirth, disease, beekeeping, planting, water, writing, and weaving. She is also the wife of the Mayan sun-god Itzamna Kinich Ahau and together they had 13 sons, 2 of which created the world and everything in it.

Her name is made up of the Mayan prefix “Ix” (meaning female) and ch’el (white faced), as befitting a moon-goddess. She is depicted in three different aspects; maiden, mother and grandmother.

When depicted as a maiden, Ixchel is often shown together with the rabbit. the Rabbit was associated by the Mayans with the moon, because when looked up in the sky and gazed at the earth’s satellite, instead of our “man-in-the-moon”, they saw a “rabbit-in-the-moon”.

Legend the 2-nd. Ixchel as a Mother.

When depicted as a mother, Ixchel often is shown carrying something strapped to her back that she is about to pass down to humanity. At times, this burden she bears is something good, like the god representing a new crop, but sometimes it is something bad, like disease or drought.

Legend the 3-rd. Ixchel as an old woman.

When depicted as an angry old woman, the goddess is known by the name “Ixchebelyax”, a name made up of the Mayan words Ix (female), cheb (brush to write with), and yax (first), or “the first lady of writing”, an allusion to her gift to mankind of the written language.

In this old-crone version of her persona, she wears a snake as a headdress, crossed bones on her skirt, and has claws instead of fingers or toes. The old hag Ixchel will  often an upturned water-jar in her hands, symbolizing the deluge she and the sky-serpent were capable of unleashing upon the world.

often an upturned water-jar in her hands, symbolizing the deluge she and the sky-serpent were capable of unleashing upon the world.

The cult of Ixchel was introduced to Cozumel by Itza Mayans when they arrived on the island in the Late Classic Period and it reached its apogee in the Post Classic, when many of the buildings in San Gervasio were erected. The cult was centered on worship and petitions to the goddess by women who came from all over the Mayan world on pilgrimages to the holy island of Cozumel. In 1549, Bishop Diego de Landa wrote that “they held Cozumel in the same veneration as we have for pilgrimages to Jerusalem and Rome, and so they used to go to visit and offer presents there, as we do to holy places; and if they did not go themselves, they always sent their offerings.”